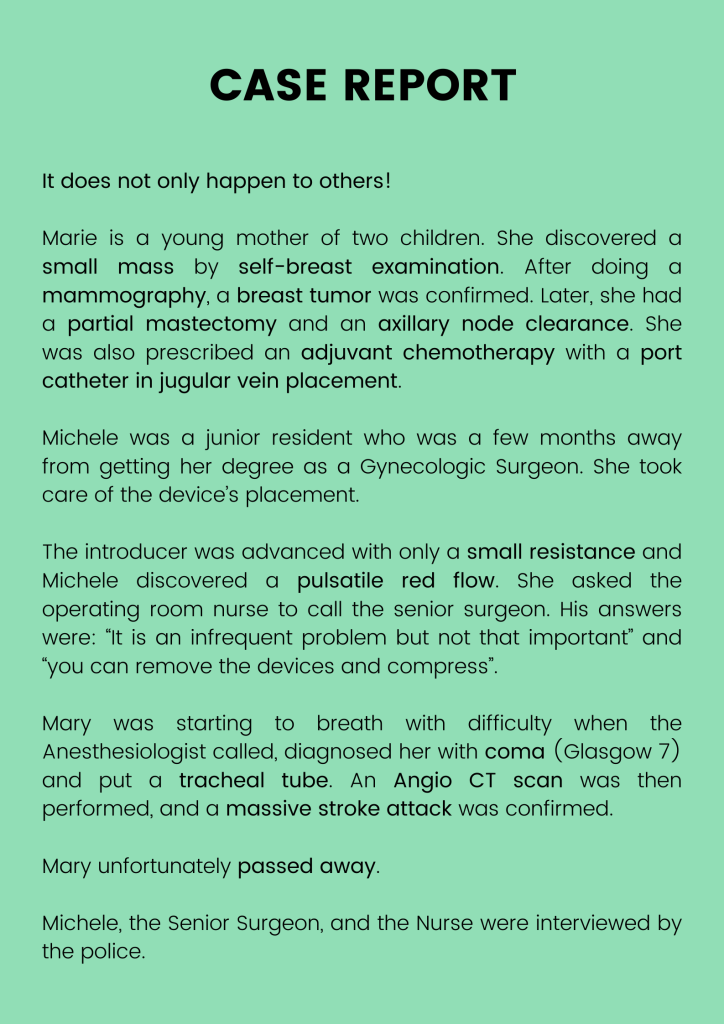

Photo 1: Case Report

Introduction

Central venous catheterization (CVC) is a technique commonly used to obtain short and long-term vascular access. There are many potential risks associated with CVC insertion and that can lead to vascular injuries.

Arterial injury or canulation is a complication that can cause potentially fatal complications; hemorrhage, cerebral ischemia, and airway-threatening hematoma formation; and is therefore a particularly feared complication.

Vascular injuries exist during CVC placements

The North American “closed claims” system, based on practitioners’ declarations to insurance companies, is a good tool for evaluating the existence of complications related to procedures and for the placement of endovascular devices too. In 2004, the inventory of complications included hemothorax, carotid wounds and canulations, and hemomediastinum. Sixty-eight percent of these events resulted in death. From 1970 to 1994, ultrasound was not yet routinely used. However, despite the use of ultrasound from 1995 to 2004, the number of complications related to this type of accident continued to increase. (1,2)

In the UK, over a period of 14 years, 26 claims were found to be related to central venous access. 14 arterial punctures, including three carotid canulations were cited. (3)

In Sweden, an analysis of complaints filed between 2009 and 2017 regarding anesthetic procedures showed that 36 could be linked to a vascular injury. This included four arterial canulations. The risk of arterial injury and occurrence of hematomas and hemothorax appeared to be correlated to the number of attempts. (4) In this series, ultrasound was used in only 20% of cases.

Thomas (2016) studied the reasons for admission to an intensive care unit (ITU) in England and Ireland over a 10-year period. During this time, it was found that 50 out of 1743 admissions were related to complications following central venous access procedures. Thirteen arterial placements were noted (only two were recognized during the procedure). Of these, four had a fluoroscopy exam interpreted as normal. (5)

The study by Lathey et al. (2017) is interesting because it was a prospective multicenter study. It was carried out over a two-week period, with a four-week follow-up, and involved 15 hospitals. All procedures (n = 487) were performed by medical specialists under ultrasound guidance. One hemothorax, one carotid canulation, and five carotid punctures were observed during the period, confirming both the existence and the rarity of these complications. The rate of artery canulation was found to be 0.2%. (6)

Guibert (7) reported the Canadian experience in 2008. After review of the literature and their own case series, a multidisciplinary consensus panel comprised of four vascular surgeons, an anesthesiologist, and an intensivist, was delegated to define the optimal therapeutic strategy to decrease the risk of complications when a large-bore catheter was inadvertently placed in an artery. Management relies on drainage, leaving dilators ⁄catheters in place to reduce bleeding, and urgent repair by surgery or interventional radiology. Thirteen cases of arterial canulation were found in their database and correlated to their 7200 central venous catheter placements resulting in an incidence of 1/1800 or 0.05%.

Returning to the clinical cases of the literature, and comparing the different models of management, they found 47% of complications in the group removed and compressed device versus none in the surgery group.

Mechanisms of vascular injuries in CVC placements

Bowdle in 2014 explained the mechanism of vascular injuries in CVC placements. (8)

First of all, the needle can injure vessels. However, the damage is largely preventable by the routine use of ultrasound to ensure accurate real-time placement of the needle tip. The quality of real-time ultrasound guidance must be good, and the needle bevel must be seen at all times during needle advancement. It is also important to recognize that arterial puncture is reduced in frequency, but not entirely eliminated. There is no difference between out of plane and in plane technique.

Secondly, guidewires, if excessive force is used, can exit the veins to pass into the pleura, mediastinum, or other structures.

Thirdly, dilators and catheters passed along a guidewire will enlarge the tract diameter. If the guidewire is kinked or angulated, and further force was applied to the dilator ⁄ catheter, they can tear the vein wall and exit into adjacent tissues. Therefore, the guidewire should be repeatedly checked to ensure that it moves freely through the dilator ⁄ catheter, freely in the lumen of the vein and to ensure no distortion.

It is important to keep in mind that fluoroscopy or radiography can be falsely reassuring. There are cases where the catheter seems to be in the superior vena cava but is in an artery or the aorta.

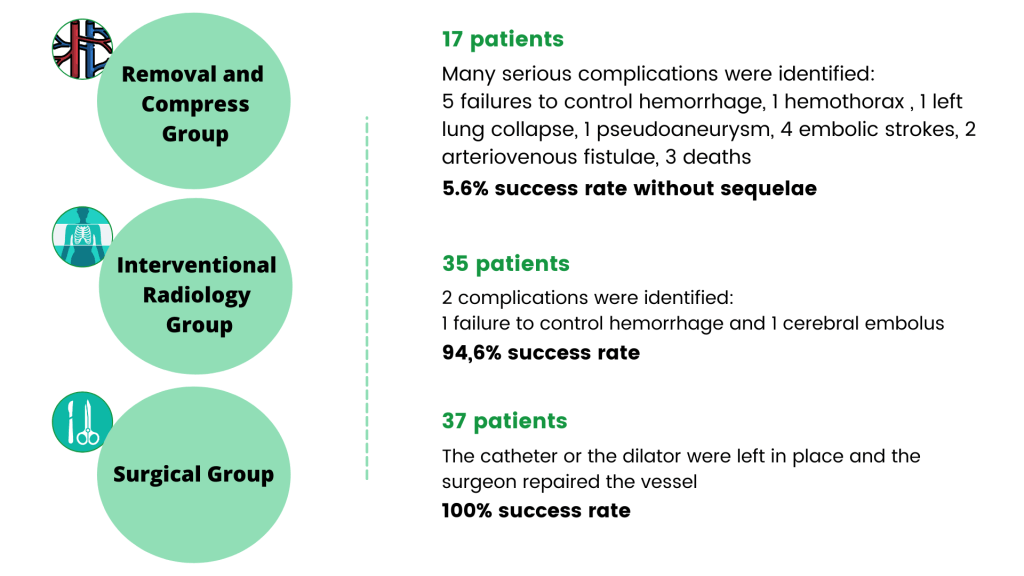

Success rate depending on intervention

In 2017, Dixon (9) reviewed clinical cases reported in the literature and found 78 incidences of vascular injuries such as arterial cannulation. He compared the survival according to the management:

Photo 2: Dixon’s (2017) review of clinical cases in the literature

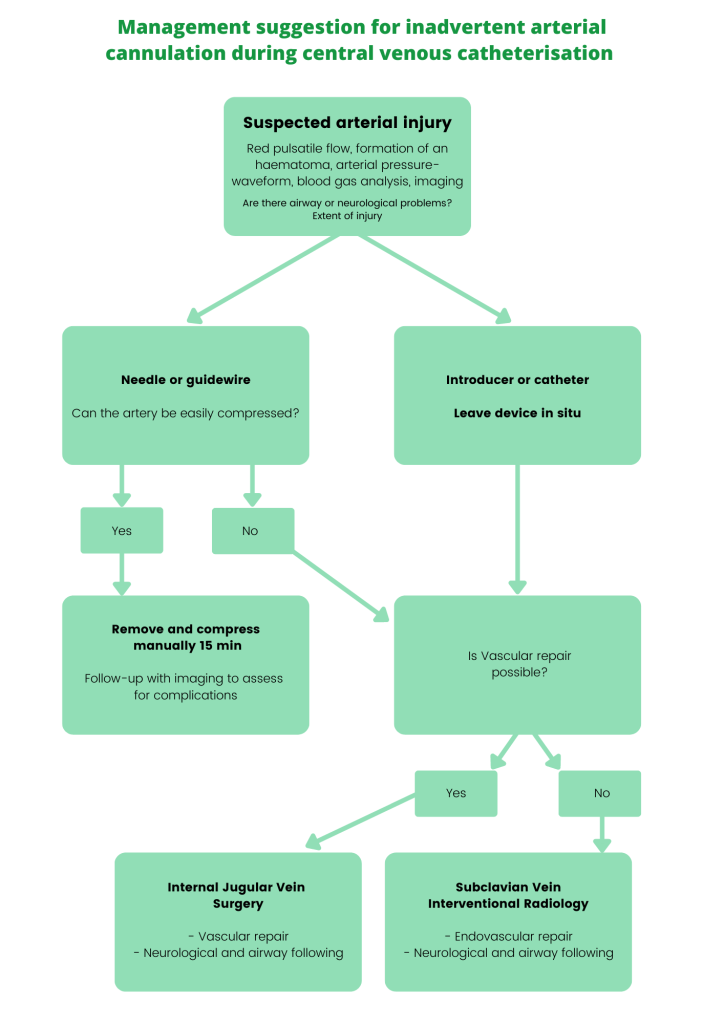

The decision tree for dealing with inadvertent arterial canulation during placement of a CVC has been described by Dixon (2007) and Guibert (2008):

- Confirm the arterial lesion by the pulsatile flow (sometimes unrecognized), by the rapid extension of a hematoma, by the measurement of blood gases, by the taking of pressures, by the imaging with ultrasound, CT or MRI.

- The patient should be regularly assessed, especially if there are airway disorders or neurological deficits.

- If there is arterial damage from the needle or guidewire, and the vessel can be easily compressed, it can be removed and compressed for 15 minutes. If the vessel is not compressible, then endovascular or surgical repair is required.

- When the arterial injury is discovered after the catheter or introducer has been placed, the hole is bigger, and a surgical or radiological opinion is required before removal.

Venous injuries also exist and can be very serious.

Collier published a six-year series of twenty one venous wounds; the operators (anesthetist, surgeon, radiologists) recall pushing the dilator completely. Sometimes, radiological documentation was available. Seventeen deaths were observed. The same decision tree should be used.

Photo 3: Conclusions on how to prevent acute vascular injuries during CICC placements

Here is the decision tree that should be put in the rooms where central lines are placed:

Photo 4: Decision tree for inadvertent arterial cannulation during CICC placements

Bibliography

– Domino KB, Bowdle TA, Posner KL, Spitellie PH, Lee LA, Cheney FW. Injuries and Liability Related to Central Vascular Catheters. Anesthesiology. 1 juin 2004;100(6):1411‑8.

– Adeogba. Central venous access complications Closed claim update. Closed Claim. (116):539‑73.

– Cook TM. Litigation related to central venous access by anaesthetists: an analysis of claims against the NHS in England 1995-2009: Correspondence. Anaesthesia. janv 2011;66(1):56‑7.

– Björkander M, Bentzer P, Schött U, Broman ME, Kander T. Mechanical complications of central venous catheter insertions: A retrospective multicenter study of incidence and risks. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. janv 2019;63(1):61‑8.

– Thomas AN, MacDonald JJ. A review of patient safety incidents reported as ‘severe’ or ‘death’ from critical care units in England and Wales between 2004 and 2014. Anaesthesia. sept 2016;71(9):1013‑23.

– Lathey RK, Jackson RE, Bodenham A, Harper D, Patle V, the Anaesthetic Audit and Research Matrix of Yorkshire (AARMY). A multicentre snapshot study of the incidence of serious procedural complications secondary to central venous catheterisation. Anaesthesia. mars 2017;72(3):328‑34.

– Guilbert M-C, Elkouri S, Bracco D, Corriveau MM, Beaudoin N, Dubois MJ, et al. Arterial trauma during central venous catheter insertion: Case series, review and proposed algorithm. J Vasc Surg. oct 2008;48(4):918‑25.

– Bowdle A. Vascular Complications of Central Venous Catheter Placement: Evidence-Based Methods for Prevention and Treatment. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. avr 2014;28(2):358‑68.

– Oliver G.B. Dixon, George E. Smith, Daniel Carradice, Ian C. Chetter. A systematic review of management of inadvertent arterial injury during central venous catheterisation. J Vasc Access 2017; 18 (2): 97-102 DOI: 10.5301/jva.5000611

– Collier PE. Prevention and treatment of dilator injuries during central venous catheter placement. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. nov 2019;7(6):789‑92.

If you liked this article, here are other pieces you may like:

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks