Although Vascular Access Devices (VAD) have many advantages, the burden of harm associated with them is significant. It is now accepted that the presence of any VAD immediately places patients at risk of complications. They can occur in all devices including a PICC and are a significant burden on healthcare workers. Most post-insertion complications are attributed to poor care and maintenance practices. According to Ullman et al. (2016), many such complications and failures are preventable. Broadhurst, Moureau and Ullman (2016) agree and claim that the prevention of complications is possible with appropriate evidence-based practices.

Over the past few decades, there have been many scientific advances in technology and techniques in the field of vascular access. In addition to advances in insertion techniques, which include the use of ultrasound guidance (Hill, 2019) and the use of electrocardiography to determine catheter tip position (Pittiruti, 2015), advances in techniques and technology for the post-insertion management of VADs have also erupted. These advances include the use of needle-free devices, securement devices, and antiseptic caps, as well as chlorhexidine-impregnated discs and dressings (Apata et al., 2017; Kelly, Jones and Kirkham, 2017; Wang, et al. 2019).

To reduce the risk of complications, morbidity, and mortality, practitioners who manage VADs need to be educated and constantly updated about correct use and care of them. Additionally, clinicians should be skilled in the strategies and methods necessary to reduce device complications (Gorski, 2021, Kelly, 2019).

This series of articles aims to increase the skills and knowledge of clinicians who are responsible for the care and maintenance of PICCs. This first article will focus on the description of the PICC and how it differs from the other long term vascular access devices.

What is a peripherally inserted central catheter?

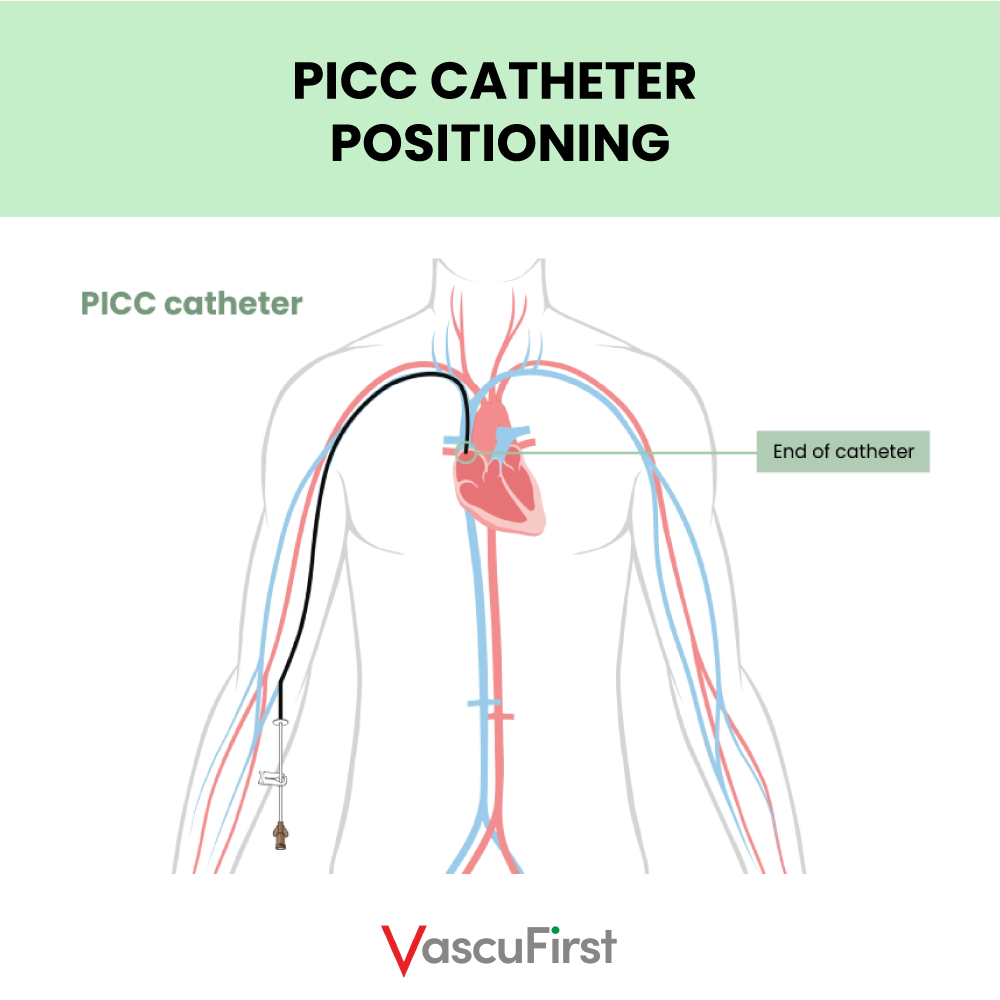

A peripherally inserted central catheter usually referred to as a PICC, is a long tube made from silicone or polyurethane. As the name suggests, PICCs are central venous access devices, meaning that the tip of the catheter terminates in one of the large central veins of the body (Figure One).

Photo 1

Photo 1

PICCs are available as a single, dual or triple lumen device. Each lumen of multi lumen PICCs should be treated as a catheter in its own right. This is because the lumens have separate fluid pathways. This means that there is no mixing of medications when delivered through the lumens. (Figure Two). PICCs can be power injectable and suitable for the delivery of contrast media via an injection pump. Additionally, some PICCs are impregnated with solutions that can help reduce the risk of infectious or thrombotic complications.

Photo 2

Photo 2

How is a PICC inserted?

Firstly, a vein of an adequate size in the middle of the upper arm is located using ultrasound guidance (Dawson, 2015, Spencer and Mahoney, 2017). The veins typically used are the basilic or brachial. Due to its small size, tortuosity and difficult path to the axillary vein, the cephalic vein is not recommended for use for PICC insertion unless there is no other option.

Once an adequate vein has been identified, a surgical aseptic non-touch technique is ensured. Full barrier precautions are required for all central venous access device (CVAD) insertions (Loveday, 2014). Therefore, the patient is draped from head to foot and the operator dons’ hat, mask, gown and sterile gloves.

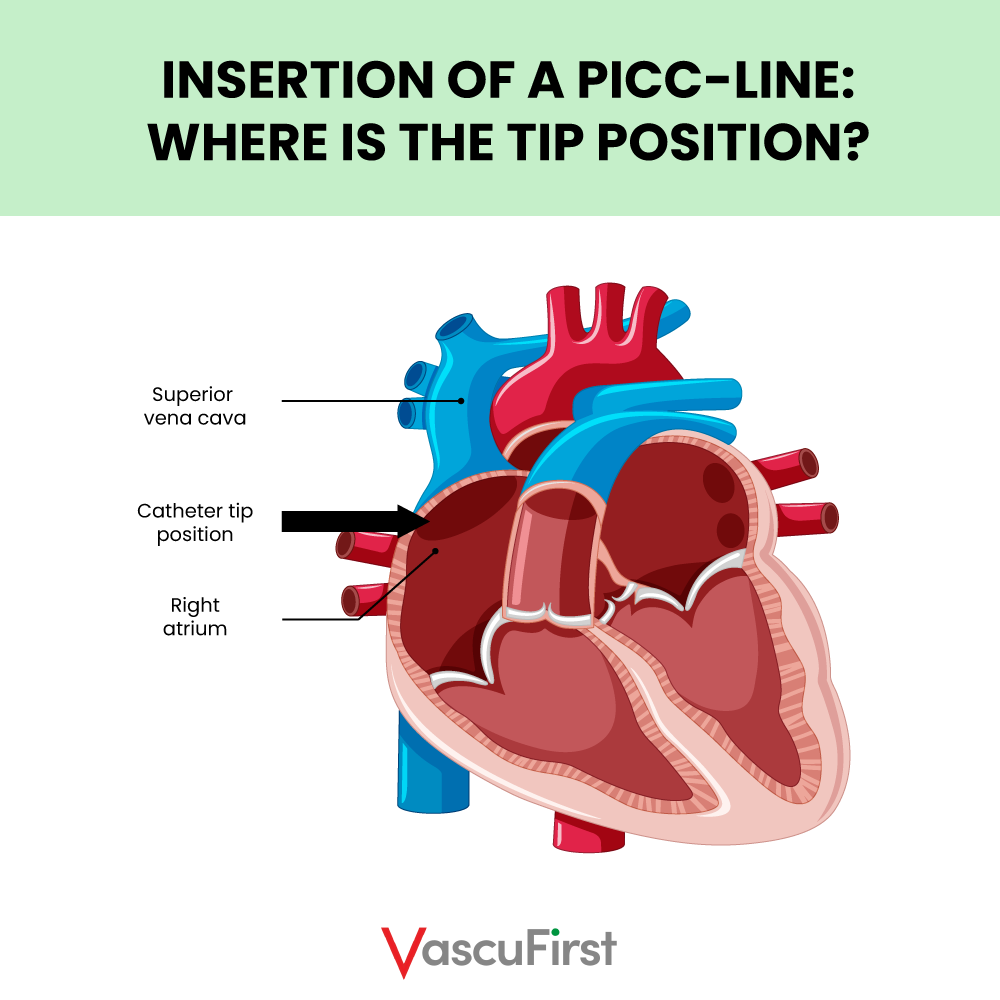

Next, using ultrasound guidance, local anaesthesia (usually 1% lignocaine) is administered subcutaneously to anaesthetise the area around the target vein. Using a Modified Seldinger Technique (MST) the catheter is advanced along the target vein, past the axillary and subclavian vein until the tip reaches lower superior vena cava (SVC) or upper right atrium (Gorski et al., 2021) (Figure Three).

The tip position of a PICC is important if thrombotic complications are to be avoided. It must be ensured that the tip of the catheter floats freely within the bloodstream in a large vein and parallel to the vein walls. Catheter to vein ratio (CVR) should be optimised to allow maximised blood flow around the catheter. This approach ensures that physical and chemical damage to the internal walls of the vein is minimised (Spencer and Mahoney, 2017).

The procedure can be performed by a range of clinicians including nurses, radiologists, ODPs, radiographers, surgeons, anaesthetists, anaesthetic associates etc. However, this is country dependent.

Photo 3

Photo 3

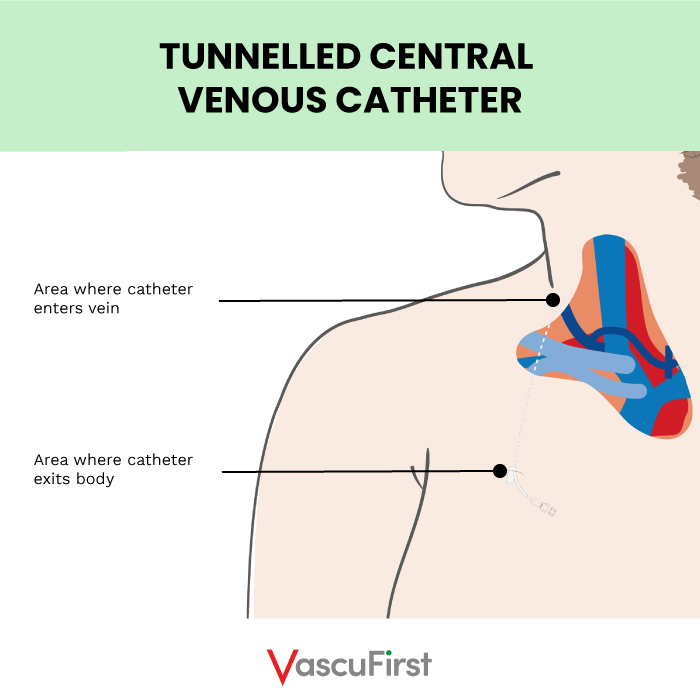

What is the difference between a PICC and a tunnelled central venous catheter TCVC?

The only difference between a PICC and a TCVC is where the device exits from the body (Figure Four). The tip of the catheter is in the same place for both. Rather than terminating from the arm, the TCVC has an entry point at the veins of the chest or neck (internal jugular or subclavian) and an exit site at the chest. In certain circumstances, a TCVC can be tunnelled to the back or entry made via the femoral vein and tunnelled onto the thigh.

Photo 4

Difference between PICC and totally implanted vascular access device (TIVAD)?

A TIVAD (port) is more similar to a TCVC than a PICC. Again, the tip of a TIVAD terminates in the lower SVC or upper right atrium (Figure Five). The TIVAD consists of a reservoir (the portal) and a tube (the catheter). The portal is typically implanted under the muscular fascia of the chest or implanted in the mid upper arm. The catheter is tunnelled before terminating in a central vein. This technique means that no part of the device is situated outside of the body.

Photo 5

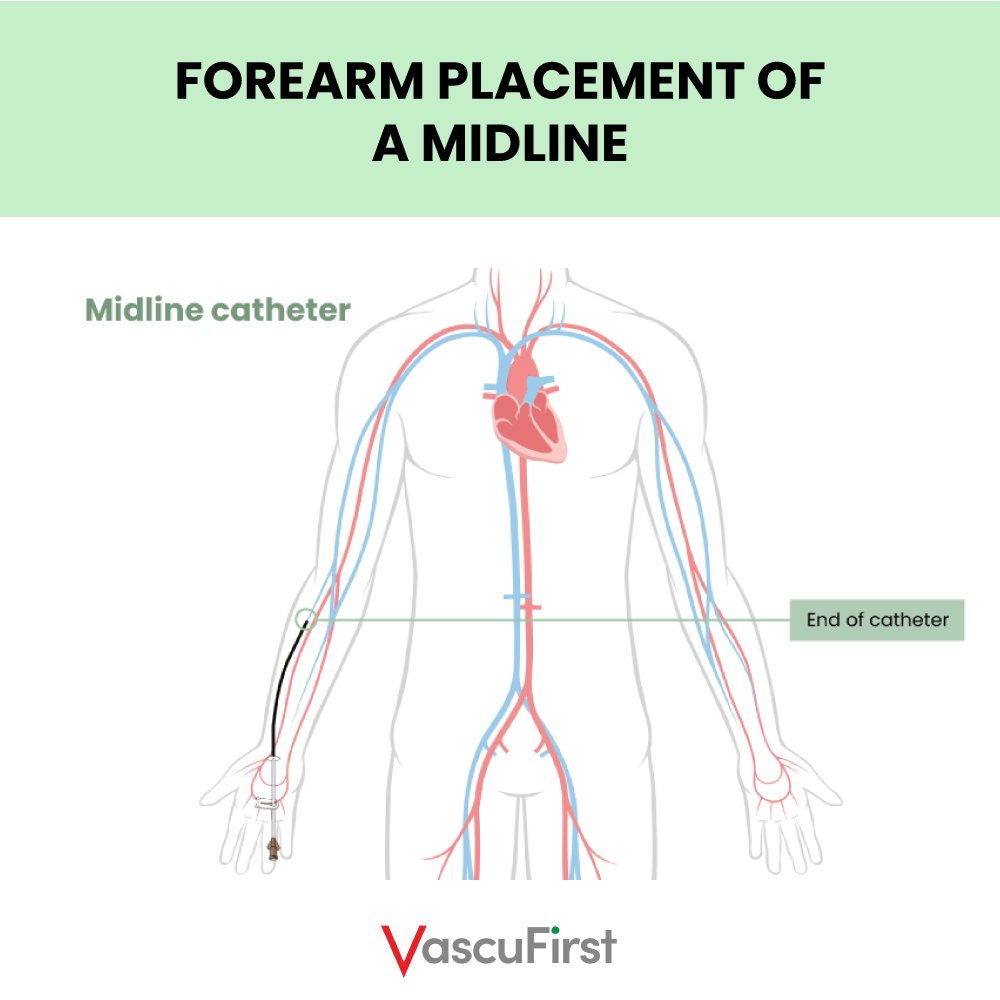

Difference between PICC and midline?

Midline catheters, often referred to as long peripheral venous catheter (PVC) or extended dwell catheters (EDC) are typically between eight and twenty-five centimetres in length. These devices can be inserted in the peripheral veins of the forearm with the tip not extending beyond the antecubital fossa (Figure six). They can also be inserted into the peripheral veins in the mid upper arm using ultrasound guidance. The distal tip of midline catheters should terminate before the axillary line. Midlines are routinely used for intravenous treatments that are peripherally compatible and required for more than five days (Gorski et al. 2021).

Therefore, it is the tip position is the most importance difference between a PICC and a midline. A midline remains a peripheral catheter as the tip terminates prior to the axillary line (before the shoulder). Whereas a PICC is a central venous catheter because its tip terminates in the lower SVC or upper right atrium.

Photo 6

Photo 6

Photo 7

Photo 7

The next article in this series will focus on the safe use of PICC.

REFERENCES

– Dawson, R. B (2011) PICC Zone Insertion Method™ (ZIM™): A Systematic Approach to Determine the Ideal Insertion Site for PICCs in the Upper Arm. Journal of the Association for Vascular Access 16 (3): 156–165.

– Denton, A. (2016) ‘Standards for infusion therapy’, Royal College of Nursing, p. 41

– Gorski, L. Hadaaway, L. Hagle, M.E et.al. (2021) Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice, 8th Edition, Journal of Infusion Nursing: January/February 2021 – Volume 44 – Issue 1S – p S1-S224

– Loveday, H.P. et al. (2014) ‘epic3: National Evidence-Based Guidelines for Preventing Healthcare-Associated Infections in NHS Hospitals in England’, Journal of Hospital Infection, 86, pp. S1–S70.

– Spencer, T. R. and Mahoney, K. J. (2017) ‘Reducing catheter-related thrombosis using a risk reduction tool centered on catheter to vessel ratio’, Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis. Springer US, 44(4), pp. 427–434

If you liked this article, you may also like:

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks